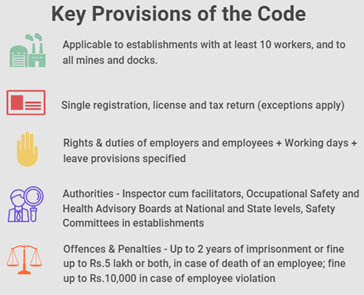

Introduced in July 2019 in the Lok Sabha as one of the four Codes aimed at labour reforms, the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code embodies an amalgam of provisions relating to safety, health, welfare and working conditions of workers by a merger of thirteen major Central laws. Abiding by the constitutional guarantees under Articles 24, 39 (e & f) and 42 and in the wake of the fatalities caused by industrial accidents and inhumane work conditions, this Code assumes great significance in laying down duties and rights of employees and their employers.

Employers are mandated to offer free annual medical examinations of all employees, issue appointment letters, and provide welfare facilities (crèches, canteen, restrooms, first aid, etc.), implement safety measures and instruct the workers on safety protocols. Employees are empowered with the right to be protected, receive information on health and safety standards and the Code demands their compliance and cooperation.

Despite recognizing a safe work environment as a basic right, the Code remains inconclusive and ambiguous on several aspects. A recent report divulged the Prime Minister’s Office to have raised objections on mandating free medical check-up of employees to be an expensive proposition for employers. Criticisms pour in over the ‘employer-centered’ nature of the Code. This sows apprehension on the final nature of the Code pending in the Parliament.

Taking the Code into the Loop

The coverage of the Code is limited to workers in certain organized and unorganized sectors of the economy who are covered under the erstwhile distinct laws. Apprentices, firms with less than ten workers, agricultural workers, police, armed forces, those earning more than Rs. 15,000 per month in supervisory positions etc., have been excluded from the ambit of the Code. Moreover, as the bulk of India’s workforce lies in the informal sector accounting for over 80% of manufacturing employment and 99% of manufacturing establishments, the efficacy of the Code is in a real predicament. Their exclusion from this safety framework will inhibit their growth and incentivize them to remain small. Additionally, while issuance of appointment letters to employees is in the interest of formalization, whether huge numbers of informal sector workers and those with open contracts be considered for the same, remains unclear.

Controversial notifications diluting labor reforms by increasing working hours in various States across India to combat the losses incurred during the nation-wide lockdown has eroded the image of the country. This has forced several States to subsequently withdraw from their earlier move. Oblivious to these possibilities, the Code does not stipulate fixed working hours for workers and has left it to the discretion of the appropriate Government. How workers’ right to health could be compromised is obvious from the ordinances passed by these States at a time when the nation is struggling to flatten the curve of the pandemic. Also, engaging in overtime work requires prior written consent of the worker. But, absence of collective bargaining power in several establishments can induce forced labor. As a result, a non uniform picture develops over the differential stipulation of leave provisions across sectors as well.

The maximum permissible limits of exposure to chemical and toxic substances in the manufacturing process in a factory has been left to the discretion of the State governments as against the Second Schedule of the erstwhile Factories Act, 1948. An explicit differentiation between maintenance of the premises, on a periodic basis from a long term process is missing from the new Code, when it has been often observed that the need for periodic maintenance is realized only in the aftermath of an accident. Despite the term ‘Occupational Diseases/Accidents’ not defined, the Code omits several important diseases in its Third Schedule such as musculoskeletal disorders, mental and behavioral diseases, diseases caused by biological agents, Miner’s Nystagmus etc., that are present in the ILO’s List of Occupational Diseases (Revised 2010).

The maximum permissible limits of exposure to chemical and toxic substances in the manufacturing process in a factory has been left to the discretion of the State governments as against the Second Schedule of the erstwhile Factories Act, 1948. An explicit differentiation between maintenance of the premises, on a periodic basis from a long term process is missing from the new Code, when it has been often observed that the need for periodic maintenance is realized only in the aftermath of an accident. Despite the term ‘Occupational Diseases/Accidents’ not defined, the Code omits several important diseases in its Third Schedule such as musculoskeletal disorders, mental and behavioral diseases, diseases caused by biological agents, Miner’s Nystagmus etc., that are present in the ILO’s List of Occupational Diseases (Revised 2010).

A closer look into the provisions of welfare facilities for workers reveals that they are optional, subject to the central government’s instructions. These arrangements are made if establishments meet the stipulated number of workers. Crèches may be set up if there are at least 50 workers, a canteen for 100+ workers and so on. The appointment of a Welfare Officer is subject to employing more than 250 workers. Such varying thresholds are visible throughout the Code. Safety Committee, a link between employers and employees with their representatives onboard are restricted to establishments with over 500 workers and mines with over 100 workers. Inevitably, a multitude of workers in several establishments will be bereft of this indispensable channel of negotiation.

The Code is also devoid of a proper judicial mechanism wherein Civil Courts are barred from hearing matters. ‘Appellate authority’ remains behind the curtains. In the case of the system of Inspector-cum-Facilitators, their jurisdiction of work and hierarchy (including subordination to a higher authority) remains vague and is left to the decision of the appropriate government.

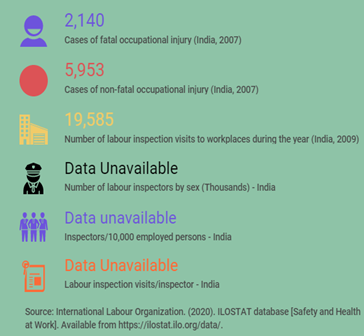

Lastly, statistical data collection, research and development in the field of occupational safety and health has been included in the Code but left unassigned to any particular expert body. A significant dearth of up-to-date information in the national and international databases leaves the entire spectrum of labor reforms under a cloud.

Standing Committee’s Report on the Code

As per the Standing Committee unclear terminology has resulted in plenty of contentions within the Code. The Committee discovered that certain core terms were undefined such as ‘wage’, ‘workplace’, ‘supervisor’ and ‘manager’ and a clear division of responsibilities by the ‘appropriate government’ leaves the draft Code incomplete. The ‘employee vs worker’ dilemma persists in the assignment of sections of the Code and a uniform interpretation throughout has been recommended. Though the designation of ‘Inspector-cum-facilitator’ was contested and alternative designations at par with global practices were suggested, this proposition was not considered by the government. Appointment of safety officers in all establishments, formation of common crèches, notification of a maximum eight hour working day, extending the coverage of the Code, separate chapters for migrant workers and plantation workers, as well as including ‘spraying pesticides/insecticides’ to the First Schedule of hazardous activities etc., are other significant suggestions. Also, for contract workers, a clear differentiation between core and non-core workers is deemed important. The Committee has thoroughly scrutinized the Code and their recommendations closely considered will aid in reforming its present employer-oriented approach.

Policy Suggestions for Overhauling the Code

- Extend the scope and coverage of the Code to cover all workers and establishments, irrespective of size, sector or status. If feasibility worries small-sized firms in providing welfare facilities mentioned in the Code, such facilities can be set up by a collective of firms located nearby for their workers and/or with the help of the local government or private CSR contributions.

- Assign a maximum of 8 hours of work in a day and rework the leave provisions acknowledging that coercing people to over-work will not enhance productivity and profits but will burden the employer later.

- A clear plan of action on the occupational health and safety measures to be undertaken in the establishment must be prepared by the employer, subject to the approval of the Inspectors and to periodic review and revision. Detailed guidelines to industries dealing with hazardous substances are to be separately laid out.

- Workers with disabilities need special consideration within the ambit of the Code.

- Toll-free helplines and help desks for reporting grievances by workers, especially migrants to the Inspector-cum-Facilitators should be introduced in every State.

- Women workers should be accorded special training, protection and rest periods as they engage in night shifts. Appointing a female Inspector-cum-facilitator will provide better agency and access to women workers.

- Periodic maintenance has to be made mandatory in the Code for all establishments, especially those dealing with hazardous substances.

- The list of notifiable diseases has to be broadened to include musculoskeletal, psychological health issues and those caused by biological agents such that their reporting will enable formulation of protective and preventive measures by the concerned Safety Boards. Integrate occupational health into the primary and secondary healthcare system. Increase focus on introduction of Occupational Health Specialists, Nurses etc. Introduce counselling services for workers as a welfare measure.

- Assign the tasks of occupational health and safety research, collection and dissemination of statistics to academic and research bodies under the supervision of the National and State Safety Boards.

- Exemptions from the provisions of the Code in the wake of a ‘public emergency’ should not be arbitrarily decided by the Central/State Governments without due negotiations with Workers’ Associations/Trade Unions.

India has not ratified all the conventions of the Occupational Safety and Health Convention of 1981 (ILO), applicable to all branches of economic activities. While mere ratification of a global convention does not guarantee enhanced safety of workers, it is high time national laws are aligned to globally accepted norms and best practices. The Supreme Court in Occupational Health and Safety Association vs Union of India & Ors (2014) emphasized the Right to Health of Workers as part of the Right to Life enshrined under Article 21. In this period of pandemic and beyond, the toiling masses especially the formal and informal labour workforce should not be overburdened. Hence, a balanced Code for the employers and employees obliges priority.

By Liz Maria Kuriakose, Research Associate, Human Rights and Social Justice