By Debarati Choudhury, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Hyderabad.

Story So Far:

The Coastal Regulation Zone Notification of 2019 has cleared the way for commercialisation and development projects in Mumbai, while racing towards a more vulnerable ecology. The proposal of lifting restrictions from over 6,070 kilometres of the coastline for commercial activities has rung alarms with many. According to the Government, “The proposed CRZ notification 2018 will lead to enhanced activities in the coastal regions thereby promoting economic growth while also respecting the conservation principles of coastal regions.” While this might seem like a win-win situation, environmentalists are wary that this will selectively benefit only a small section, and adversely affect all coastal communities through predictable yet inevitable weather changes and a steep rise in sea level.

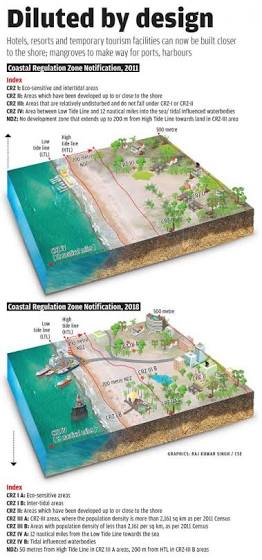

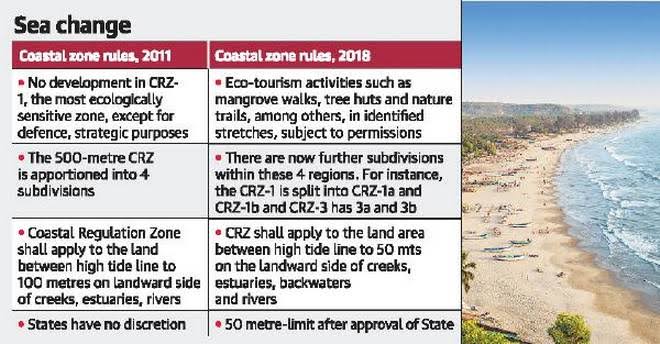

The coastal zone regulations were issued in 1991 under the Environmental Protection Act, 1986. It aimed at regulating and maintaining a roof over the pressure of urbanisation, population and development on the ecology. Depending on the regulation and the climatic and land sensitivity, the area was divided into 4 categories- CRZ-I, II, III and IV.

In 2004, after examining the extent of devastation caused by the Tsunami, efforts were made to revamp the regulations. The same can be seen in the CRZ notification of 2011, where CRZ-1 that includes the most ecologically sensitive areas like mangroves, coral reefs and sand dunes, was absolutely restricted from tourism and developmental activities.

Source: Down to Earth

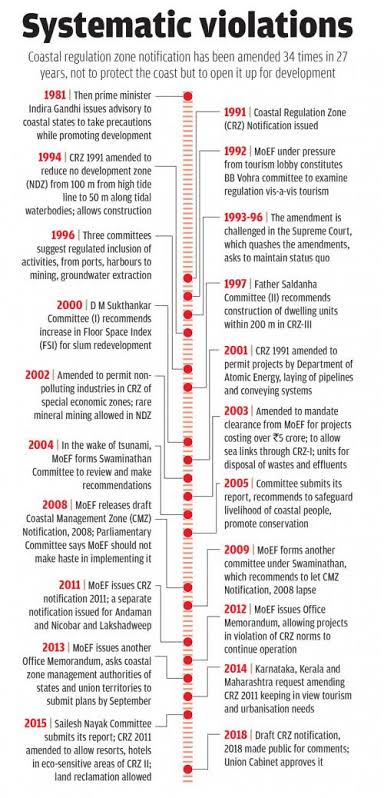

Since then, there has been only dilution in the CRZ Rules. It is infamously the most amended regulations in the Indian context, with 34 amendments over the last 28 years. The latest notification has been extremely violative in the sense that it allows “eco-tourism activities such as mangrove walks, tree huts, nature trails, etc” in CRZ-IA, constituting some of the most eco-sensitive areas. CRZ-IB allows new land to be created from the ocean or lake beds. Construction of resorts was absolutely restricted within the No Development Zone of CRZ-III, but now the area of the same has been reduced to just 50 metres from the High Tide Line.

Source: The Hindu

The CRZ-IV (belt of coastal waters extending up to 12 nautical miles) constitutes the most important fishing zone, providing livelihoods to the entire fishing community. This is also a region that is most prone to deposition of man-made wastes from offshore activities like mining, oil exploration and shipping. With the recent changes, there is no prohibition on “reclamation for setting up ports, harbours and roads; facilities for discharging treated effluents; transfer of hazardous substances; and construction of memorials or monuments”.

The notification completely ignores the livelihoods of over 170 million people, 7% of who belong to the fishing communities. All fishing activities will henceforth be controlled, mostly in CRZ-III where the community resides. Further, the shift of CRZ-IV from under the State jurisdiction to the Centre has centralised the mechanism. Earlier, people could question the State authorities for grievance redressal, but now, the State has no powers in this respect. This would diminish the voices of the fishing communities and their concerns and grievances might not be addressed adequately. The government used satellite imagery to demarcate the zones, without meeting the people on the ground, thereby conveniently ignoring the possible effects on their traditional seasonal activities and conflicts in the future.

Development Projects contravening the Coastlines:

The Ministry of Shipping launched the Sagarmala programme in 2015. It aimed to promote port-led development by utilising the “7,500 km long coastline, and 14,500 km of potentially navigable waterways and strategic location on key international maritime trade routes.” 550 projects have been identified worth Rs 8 lakh crore; Sagarmala also plans to set up 14 coastal economic zones to increase industrial growth.

The Indian coastline faces the most erosion during the monsoon months. During this time, high-tide waves drag soil away from the shore. After the monsoon is over, low tide waves bring back the eroded sediment and soil. The cyclical process of erosion and accretion ensures that the beaches remain intact. However, as the sea becomes more violent due to climate change and urbanisation activities, less sediment is returned by the waves, which narrows the width of the beach. Under these circumstances, Sagarmala Project will inevitably accentuate the irreversible process of coastal erosion. Moreover, due to the Project, local fishing communities have now been relocated and thus have to anchor their boats far away, with the increased transportation costs affecting their incomes. However, Sagarmala has a meagre allocation of Rs 1,415 crore towards development of the coastal communities, which is 0.36% of the total intended expenditure.

There is also the proposed coastal road project of Mumbai with an estimated cost of Rs. 14,000 crore. The project plan was initially just a bypass route, but now it has transformed into a multi lane transport route with bridges, bus rapid transit system corridors, a 3.4-km tunnel (from Khar Danda to Juhu) and interchanges at several points.

The project received a severe backlash from environmental activists and the fishing communities. Giving due recognition to the petitions filed by the concerned parties, the Bombay High Court quashed the environmental clearance granted to the project, citing lacuna in the decision-making process and highlighting the need of a scientific study before initiating such a commercialisation project.

Unlike Mumbai, no other coastal region has a strong case going against the development programmes. NDTV had filed a petition before the National Green Tribunal, asking for measures be taken for the Indian coastline to be protected. They asked for a stay order on all the new ports construction activities across the country as part of the Sagarmala project, till the tribunal gives a verdict. But soon after, the petition was withdrawn and no other petitions were filed thereafter. The concerns for coastline protection and preservation is thus largely restricted to the groups of fishermen, environmental activists and academicians.

Heeding our Coastal Zones in an Ecologically Sensitive World:

The Central Water Commission’s Shoreline Change Atlas states that India has lost 45% of its coastline, from 1990 to 2006. Although waves and currents continue to be the main reason behind the erosion of the coastline, human activities like harbour dredging, constructing seawalls, groynes and jetties, reclamation of land, tidal inlets and navigational channels have sped up the process in manifolds.

Earlier it was possible to predict a storm by examining the cloud, the moon and the sea-level. Now storms come all of a sudden. Weather changes are becoming unpredictable with every passing day. The rise in sea level, aggravated by developmental and commercialisation projects, is resulting in fast erosion of the coast. We are paving the way for the extinction of a rich coastal biodiversity, the foremost examples being the Bombay duck on the western coast, and the Hilsa along the eastern coast. This is part of the larger environmental distress that the world is facing at the moment. But the people who are being drastically affected by this are the small-scale fishermen. A decrease in the coastal fish stock automatically translates to a loss of livelihood for them. For instance, in Jambudwip in the Sundarbans, 10,000 fishers have already lost their livelihood.

In such a backdrop, the need of the hour is a strict coastal policy that would emphasise on planned treatment of sewage and disposal of wastes, and contribute to conserving and developing the ecology and community along the entire coastline of the country. One should also strictly maintain the following:

- CRZ-I A is environmentally the most sensitive and critical, this area should be completely exempt from any construction or commercialisation activities.

- CRZ limits on land along the tidal influenced water bodies must be increased to 100 metres. Construction of resorts must be absolutely restricted within the No Development Zone of CRZ-III.

- There is no mention about Koliwadas, which are the fishing settlement areas in Mumbai and had special protection in the 2011 notification. Safeguards for the fishing community must be put in place to ensure a stable and dignified livelihood opportunity for them.

- CRZ-IV constitutes the most important fishing zone. Sewage must be treated and unnecessary dumping of industrial wastes must be regulated here to prevent destruction of biodiversity.

- The 2018 draft regulations elaborate on the procedures to be followed to obtain clearances for the erection of monuments and memorials in the sea. It also mentions that the government can waive off the public hearing if a project is sufficiently important. Under no circumstances should a public hearing be infringed upon, because that is the only grievance redressal available for the affected parties.

Tracing back to the aim of the government to develop the coastline areas, one should ask the question of “whose development are we talking about?” and “at what cost is this development happening?” The current trends in commercialisation almost ignore the drastic repercussions, and their irreversibility, on the environment. These urbanisation programmes are hence very shortsighted and concentrated on earning immediate profits. The market is destroying small-scale indigenous fishing communities, consolidating the position of MNCs and national multibillion corporations, who honestly do not have knowledge about preservation of the ecology. The future of our environment is thus very gloomy if the present development practitioners and urbanisation programme managers do not take into account the ecological balance that supports all living forms in the world.