The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 has again brought to light the lengthy debate and discourse on the need for enhanced policies to improve our educational system. A report by UNESCO, namely ‘No Teacher, No Class: State of the Education Report for India 2021’, discusses the various facets and spheres of India’s teaching and educational system, ranging from employment status topics to teaching practices. The report has made some inferences using secondary data such as Unified District Information System for Education (UDISE+) and Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS). This article focuses on chapter two from the report, namely ‘Profile of Teachers in India.’

The chapter discusses the availability and deployment of teachers in India; according to the report, the efforts to improve educational accessibility have been fruitful as there has been an increase in the number of teachers and schools. When it comes to the types of schools, they vary in terms of the grade included in the school, their administration, and the medium of instruction. PLFS 2018/19 data shows that the percentage of teachers working in rural schools varies according to the education level.

An essential parameter for quality education is the Pupil-Teacher Ratio (PTR). Under the Right to Education Act, the norm laid down for PTR is 30:1 for grades 1 to 5 (primary) and 35:1 for grades 6 to 8 (middle school/upper primary). However, it is found that these numbers do not reflect the ratios at the school level. An essential concern is that the PTR at secondary and senior secondary levels is abysmal.

There are fewer single-teacher schools in the country, most of which are situated in rural areas. While single-teacher schools are better than no schools, the education imparted can lack substantive learning. This is because a teacher has to teach students multiple subjects in a single teacher school, including those beyond the teacher’s expertise. Along with this, the teacher also has to teach students of different grades on their own. Such a situation cannot lead to quality education and learning.

There is also the absence of essential data on vacancy requirements. This is a point of concern because a proper mechanism must be in place to record the vacancies available across the country; this can help streamline the recruitment of teachers.

Yet another essential aspect of quality for an enhanced educational experience are composite schools, as they provide specialized and varied teachers for various academic and non-academic disciplines. The number of government school teachers working in composite schools is abysmally low at only 2 percent. The lack of composite schools can restrict the students from having a holistic education experience and hinder an enriching teaching experience.

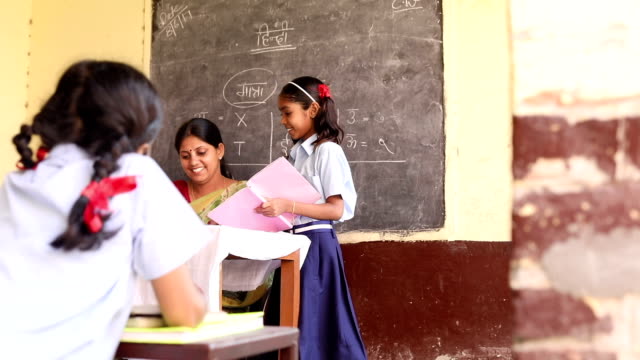

There has been improvement in the number of schools and teachers in India (SOURCE: Pradeep Gaur/ Mint)

A diverse school environment is also vital since it ensures equitable opportunities for all communities. As mentioned in the report, at the time of independence, most of the teaching workforce comprised men of upper castes and social groups; however, with policies like Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), the National Policy on Education (NPE) 1986, and Operation Blackboard, there has been an increase in the number of females and individuals from marginalized communities in the teaching sector. Women account for around half of the teaching workforce; however, there is a diversity in State-wise, urban-rural comparisons. Many States with a high percentage of women teachers have performed better on the Performance Grading Index (PGI). It is also noted that the sectors like early childhood education have the most number of women teachers. This is an outstanding achievement because more women teachers help increase the number of girls enrolling in schools and help bridge the gender gap. However, many have also pointed out that there are fewer female teachers at higher levels and senior positions like that of professors.

Teachers from marginalized groups such as Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBC) are better represented in the early childhood education, primary and secondary sector. However, they are still not well-represented in vocational and special education sectors, with a shocking 0 percent in the latter for both ST and SC groups according to the PLFS 2018/19 data. As mentioned in the report, according to a study by Rawal and Kingdon (2010), a student had higher achievements in a particular subject when the teacher was of the same gender, caste, or religion as theirs. Hence, ensuring that all communities get equal representation and opportunities is essential.

The teaching sector has a gender balance; in fact, some sections in the sector are highly feminized. (SOURCE: GODONG/ ROBERTHARDING VIA GETTY IMAGES)

Professional qualifications have also become a mandated requirement to be an eligible teacher in schools. The National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE) has regulations that include: academic qualification, professional qualification, and passing the teacher eligibility test (TET). However, due to policies for more comprehensive educational access, sometimes the standard for qualifications of teachers has been reduced. According to data from UDISE+ (2019/20), the most significant proportion of unqualified teachers was in the unaided private sector. However, almost all States have Teacher Eligibility Test (TET) as a mandatory requirement.

Single-teacher schools and less qualified teachers also indicate a lack of teachers and, most importantly, of qualified teachers. Measures like single teacher schools and recruiting less qualified teachers can provide temporary relief but can be detrimental for the student’s future in the long run.

The report also discusses the importance of providing a ‘supportive service environment,’ core to the UNESCO teacher policy guidelines (2015). The report notes that there have been improvements in basic amenities such as electricity, drinking water, toilet facilities, and road accessibility; however, there is room for improvement, especially in the North-Eastern States (along with some other States). For classroom environments, however, there is a need for overall improvement.

In terms of professional work environment and educational supplies, free textbook availability is at 78 percent overall but low in the North-Eastern States. Library facilities need to improve, and ICT facilities are also at meager numbers. Academic visits by the supervisor are overall at 76 percent; however, States like Bihar, Nagaland, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal have low supervision visits.

The discussed report has shed light on some obstacles in India’s journey towards quality education. These obstacles need serious attention. Having one of the world’s youngest populations, India has a demographic advantage that can be leveraged with quality educational policies. Hopefully, this advantage can be leveraged with the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020. Education is the most revolutionary tool a nation can use to walk towards the path of progress. It has been proven time and again that education can be a significant force for economic development. It is time to prioritize development by focusing on improving education outcomes and making strides in our journey to grow as a nation.

Author: Shweta Rasaily, Research Associate, Policy, LQF

Note: Please support LQF’s work to uplift the underprivileged and marginalized by making a donation through the button below.