The importance of accessing quality education lies in the purpose, utility, and role that education plays in the development of human beings. Scriptures, scholars, and Courts have cited many reasons for the importance of education. One such reason is that it facilitates the development of the human personality and qualitative improvement of life. Another reason is that education plays a role in mitigating social exclusion. The New India Literacy Programme (NILP), approved by the Ministry of Education for the next five years, notes this interconnectedness between learning and the holistic development of citizens of the 21st century in its objectives. The NILP derives its goals from the latest National Education Policy (NEP 2020), wherein the curriculum for Adult Education and Lifelong learning is set to include not only foundational literacy, numeracy, and basic education but also critical life skills such as financial and digital literacy, as well as vocational skills helpful in securing local employment. In addition to these categories, the scheme aims at providing continuing education courses in areas including arts, sciences, technology, culture, and topics of local significance. At the very outset, the program seeks to replace the usage of the terms ‘Adult Education’ with the terms ‘Education for All’ to bring focus to the population of non-literates above 15 years of age, although not adults, who intuitively are not considered to fall under the scope of the term adult education.

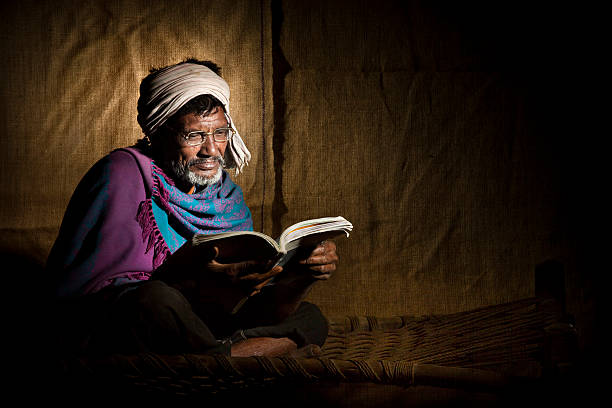

Image: State of literacy in Rural India (Source: Getty Images)

Historically, adult education in India only gained particular importance in the 1960s. Before this, the predominant focus of education policy was on primary education. An experimental program developed by UNESCO supported India in integrating literacy with knowledge relevant to the occupation of the learners, broadly understood as ‘functional literacy.’ Operationalized through the Farmer Training and Functional Literacy Program, functional literacy concerning the efficient use of HYV seeds in the context of the Green Revolution was deemed crucial to the enhanced agricultural production seen in the country.

During the decades that followed, with the National Adult Education Programme (1978), the National Education Policy (1986), and the National Literacy Mission (1988), the focus expanded from merely functional literacy to a combination of learning that not only brought about foundational literacy but a social awareness that would enable the poor to be active participants in development as opposed to being passive bystanders. Conceptually, the NILP and NEP 2020 are located within the aforementioned understanding of literacy. At this stage, we can look at some of the salient features of the program.

Defining features of the NILP

The program will be carried out using a Jan Andolan (mass movement) wherein three crore students from 7 lakh schools registered under the Unified District Information System for Education (UDISE) and 50 lakh teachers from government-aided and private schools will participate as volunteers. The use of volunteers to spearhead literacy programs has proven effective in the past. A notable example is the mass literacy campaign mobilized in the Ernakulam District of Kerala, wherein the joint effort of a Non-Profit Organization, the District Administration, and Mass Volunteerism brought about total literacy in the District within the time frame of a year. Secondly, the program is set to be carried out in an online format leveraging the use of technology through, what is referred to as, an Online Teaching, Learning and Assessment System (OTLAS) in collaboration with the National Informatics Center, NCERT, and NIOS. The resource material for volunteers for the said program is set to be provided digitally through various modalities, including the television, radio, applications (Apps), and portals available on cell phones free of cost.

In terms of quantitative achievements, the program targets five crore learners at the cost of INR 1 crore per year, using schools as the unit for conducting surveys of beneficiaries and volunteering teachers. Further, an annual achievement survey has been proposed to assess the achievement of the learning outcomes of the scheme from each State or Union Territory by use of randomized samples of 500-1000 learners. The NEP 2020 on adult education states that a body within the NCERT will be responsible for laying down the curriculum based on the objectives previously mentioned. The public release of the program also says that the assessment of literacy is to be conducted through a scientific format that would “capture real-life learnings and skills for functional literacy.”

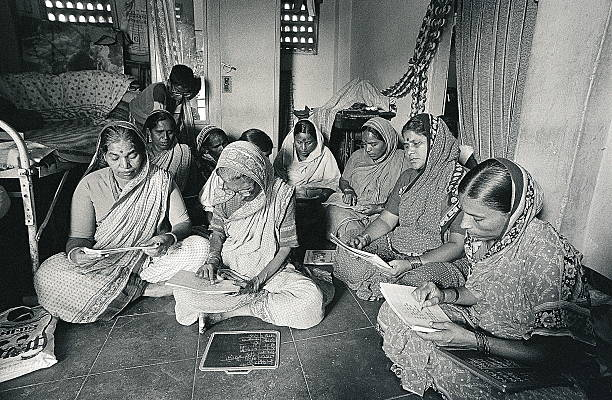

Image: Portraying Adult Literacy Drives in 1990 (Source: India Today Archives)

Considerations

A review of the literature on adult education programs in India provides further perspective on the key issues that must be given importance for the program to be a success:

- In the past, the focus of literacy campaigns has been directed to elementary literacy skills and less on functional skills and knowledge.

- A primary barrier to adult education is the lack of incentive for learners to undergo foundational literacy in the absence of a commitment to a strong link between such literacy and vocational skills, which would garner more participation. In this context, it would be crucial to ensure that there is an evaluation of the qualitative achievement of the scheme.

- There is a need to view adult education as an ongoing activity, requiring permanent professional institutions to train the workforce.

Adult education programs and policies in the past have been conceived and implemented as short-term projects, thereby not viewing adult illiteracy as a mainstream concern. The latest data on adult literacy rates shows that India is home to 26 crore non-literate people above 15. This figure includes 17 crore females and nine crores males. While the Union Budget for the financial year reflects a more excellent distribution of funds to education as a whole, it is desirable for there to be a concerted effort in ensuring that the NILP does not become merely tokenistic.

By Shruti Mittal, Research Associate, Law, LQF

Note: Please support LQF’s work to uplift the underprivileged and marginalized by making a donation through the button below.